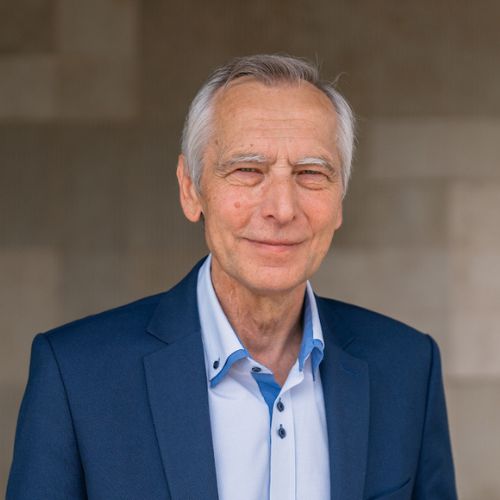

Author: Marek Olšanský

-

European Court Dismisses Challenge to Slovakia’s COVID Worship Bans

Strasbourg (4 September 2025) – In a disappointing decision for religious freedom, the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) has ruled Dr. Ján Figeľ’s challenge to Slovakia’s sweeping bans on communal worship during the COVID-19 pandemic inadmissible. The Court concluded that it would not rule on the merits of Figeľs challenge because it was not sufficiently clear how Figeľ himself was negatively impacted by the measures taken

-

家庭連合解散決定は「恣意的」 国連勧告無視に警鐘 前EU信教の自由特使 ヤン・フィゲル氏(上)

東京地裁は3月、民法上の不法行為を根拠に世界平和統一家庭連合(家庭連合、旧統一教会)に解散を命じる判断を下した。教団は即時抗告し、現在、東京高裁で審議されている。前欧州連合(EU)信教の自由特使のヤン・フィゲル元スロバキア副首相がこのほど、本紙のインタビューに応じ、決定の問題点や信教の自由の意義について語った。(聞き手=ワシントン山崎洋介)

-

Former EU Envoy: Arbitrary Dissolution Order

Tokyo District Court’s Ruling on Family Federation is arbitrary, unconstitutional, and politically driven, says former EU Religious Freedom Envoy Jan Figel Tokyo, 2nd September 2025 – Published as an article in the Japanese newspaper Sekai Nippo. Republished with permission. Translated from Japanese. Original article. [Part 1 of interview with Jan Figel, Former EU Special Envoy for Freedom

-

Figeľ: Samit na Aljaške by mal presiahnuť mier na Ukrajine a viesť k novej európskej jednote

Podľa Jána Figeľa je potrebné prekonať súčasné výzvy prostredníctvom spravodlivých rokovaní, ktoré zahŕňajú postupné kroky. 17. 08. 2025 12:12 Samit medzi prezidentmi USA a Ruska na Aljaške predstavuje jedinečnú príležitosť na obnovenie dialógu medzi hlavnými mocnosťami euroatlantickej oblasti, tiež ukončenie dlhodobého konfliktu na Ukrajine a studenej vojny, ktorá trvá od roku 2014. Na webe diplomatmagazine.eu to uviedol bývalý eurokomisár

-

Alaska Summit Should Go beyond Peace in Ukraine

By Ján Figeľ The summit of the US and Russian presidents in Alaska is an extraordinary opportunity to launch a renewed and productive dialogue between the main powers of the Euro-Atlantic area. It can lead to the end of damaging development and long confrontation: the bloody war in Ukraine since 2022 and the (second) Cold

-

Politické fórum / Náležité ocenenie

Poľsko udelilo Jánovi Figeľovi vysoké štátne vyznamenanie. Na konci júla prebehla mnohými médiami správa o tom, že Jánovi Figeľovi udelil poľský prezident Andrzej Duda vysoké štátne vyznamenanie – Rytiersky kríž za zásluhy o Poľskú republiku. Okrem úprimnej gratulácie svojmu predchodcovi vo vedení KDH chcem týmto textom vyjadriť niekoľko pohľadov na desaťročia národného, európskeho a medzinárodného

-

Combating Hate Speech: The True Beginning of Peace and Human Dignity

By Diplomat Magazine – July 30, 2025 “Peace is built in the heart.” Pope Leo XIV “War begins with words.” Sheikh Abdallah bin Bayyah By Jan Figel and Sheikh Al Mahfoudh bin Bayyah In an age marked by overlapping crises – from armed conflicts and ideological extremism to ethical breakdowns in public discourse – a need to return to

-

Figeľ si prevzal vysoké poľské štátne vyznamenanie, prezident Duda ho udelil aj ďalším dvom Slovákom – FOTO

Boli ocenení Rytierskym krížom rádu zásluh Poľskej republiky za mimoriadne zásluhy pri rozvíjaní medzinárodnej spolupráce a za aktivity na podporu hnutí za nezávislosť v strednej Európe. Poľský prezident Andrzej Duda udelil vysoké štátne vyznamenanie Jánovi Figeľovi, Jánovi Hudackému a Pavlovi Mačalovi. Ako na sociálnej sieti Facebook informuje Veľvyslanectvo Poľskej republiky v Bratislave, boli ocenení Rytierskym krížom rádu zásluh Poľskej republiky

-

Čo hovoria na hlasovanie KDH o novele ústavy a dvoch rebelov exlídri hnutia?

Novela ústavy o kultúrno-etických otázkach sa zasekla na dvoch poslancoch, „odbojároch“ v KDH. Bývalí špičkoví politici hnutia Pavol Hrušovský, Ján Figeľ, Ján Čarnogurský a Vladimír Palko hodnotia v ankete Štandardu hlasovanie KDH v parlamente. O vládnom návrhu sa má definitívne hlasovať v treťom čítaní v septembri. Parlament odložil konečné rozhodnutie, pretože sa našlo len 89

-

Is the EU fading from History?

The text is based on a keynote speech at the Colloquium organized on 26 May 2025 by the Institute Jean Lecanuet in Paris The question about EU’s fading from history is a timely warning. Brexit confirmed it. The situation of the EU and its Member States is serious – they face war and military conflict